Part 1 in a series of 6 blogs navigating the issues around vaccinations

Christians are committed to health! Of course, we live with the reality of sickness and death, but healing was central to Christ’s ministry.

His healings showed that the kingdom which he was bringing would mean restoration and the end of death and pain and suffering. Jesus’ follower has always seen the importance of caring for the sick and praying for healing — looking forward to the day when full healing will come. Christians have been in the front line of medical care and medical developments ever since. For a Christian, healthcare practices cannot be separated from the overarching commands to love God and love our neighbour.

Vaccination provides a very practical way in which we can serve our neighbours and contribute to the common good. It is not first of all about protecting ourselves. That is because vaccination is effective through ‘herd immunity’ or as “community immunity”. These terms have become common during the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding what they mean is the key to seeing how important vaccination is, and how it serves a whole community.

The origin of the term is the observation that ‘herd’ animals protect the vulnerable in their midst by exposing the stronger animals in the herd to the outside threat. Vaccination works in a similar way. If enough people are vaccinated, even those who are not able to be vaccinated are protected from infection. There’s a helpful video on YouTube that explains how this strategy works. https://youtu.be/rAGHXMq9ttw

Vaccination usually involves the introduction of a weak or dead form of the microbe (a virus or bacteria), or a part of it, into the body. This triggers the body’s natural immune process which produces antibodies which resist the infection. It is as if the antibodies can remember the microbe and destroy it whenever they find it in the body. The result is that the person is immune from the microbe. They will not become ill, or will be far less ill, even if they encounter the infection.

There will, however, always be some people who are not or cannot be vaccinated, or for whom vaccine is not effective. People with a compromised immune system usually cannot be vaccinated There will be some people who are too sick to receive the vaccine, and the very young and the elderly will probably not be vaccinated. There may also be some groups who are not vaccinated because they have limited access to medical services. Often these people are the most at risk from an infection. It is these people who particularly benefit from herd immunity.

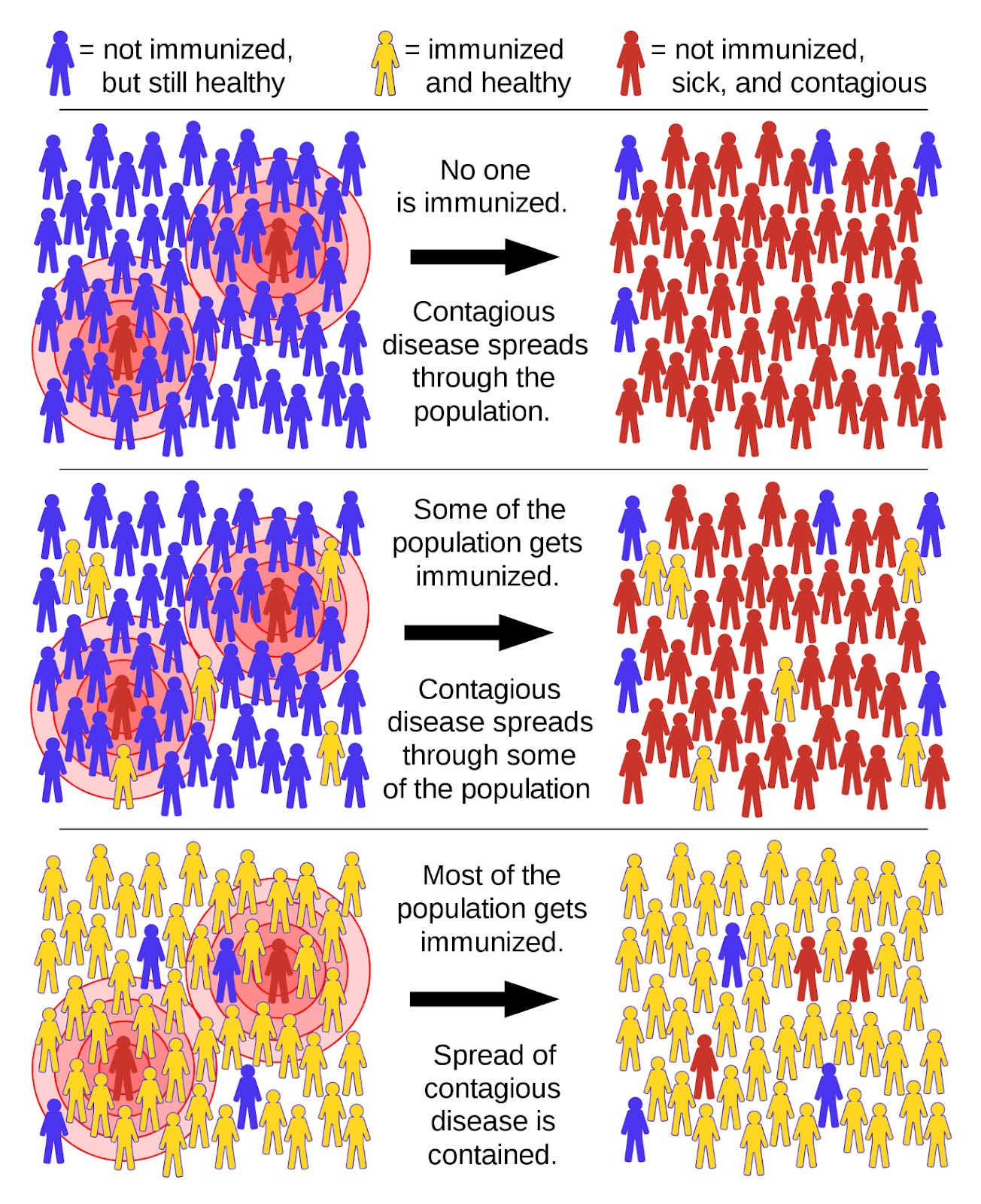

The illustration below shows the effect of increasing the number of immunised individuals in a population. In the top row, we see a community without immunity; in the middle row, a community with some immunity; in the bottom row, a community with threshold immunity. In all three scenarios, the infection is present but the risk to the population, especially those who are vulnerable, is considerably different. Vaccination is the most effective strategy to reach threshold immunity in a community.

Figure: Image based on an illustration by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, and used under the Creative Commons, CC-SA 4.0 licence

Read Blog 2 in the series here

Read Blog 3 in the series here

Read Blog 4 in the series here

Read Blog 5 in the series here

Read Blog 6 in the series here

The principle is simple: when enough people are protected or immunised, the vulnerable members of the community will be protected because the spread of the virus is decreased. Herd immunity is achieved because the immunised individuals who encounter the disease will not get sick, nor will they spread the disease any further.

The more individuals who are immunised, the fewer will be susceptible to the infection. And this means the infection cannot spread uncontrollably through the community. The infectious microbe will still be present in the community, but its transmission and spread are halted.

Alternatively, when few people are vaccinated, the immunity of the whole community is limited, and we can expect the infection to spread, especially among those not able to survive the disease.

The proportion of the community that must be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity varies for different viruses and bacteria, ranging from 70-to-90% of the population. Measles and pertussis (whooping cough), for example, require a high proportion of the community to be immunised (94-95% ) to interrupt the spread of the disease. Where immunisation numbers are low, there have been examples of outbreaks in recent years. In 2019, there was a measles outbreak in the USA due to an unvaccinated tourist at Disneyland (read here). More recently, and closer home, was the plight of Samoa where a State of Emergency was declared because of more than 1,000 suspected cases of measles and 32 related child deaths (read more on the UNICEF website). And in Australia, in communities where childhood vaccination rates are lower than in others, there has been concern about outbreaks of diseases such as whooping cough (We’re a sniff away from measles epidemic)

Of course, we do not currently have a vaccine for COVID-19. There has been discussion about the possibility of developing herd immunity by simply allowing the virus to circulate. This has been the strategy pursued in Sweden. One major problem with this strategy is that it puts a large burden on the vulnerable in the society. Between 40%–to-50% of the cases in Sweden have been elderly nursing home resident population and there has been a very high death rate. (It is fair to note that there is ongoing debate about how to assess this death rate). A further challenge is that there is still a great deal to learn about how our bodies respond to the virus. Is it possible, for example, to be infected a second time by this virus?

All in all, the approach of Australia and many other nation to actively suppress the spread of virus while waiting for a vaccine seems far wiser.

The proverb is right: Prevention is better than cure.

One of the challenges of developing a vaccine for COVID is it is caused by a corona virus which will probably mutate, like the ’flu virus. This means that a vaccine is effective for only a short time before a new strain is circulating in the community. That is why doctors recommended we get a new ‘flu shot’ each year. It might turn out that a COVID vaccine is similar.

How should Christians approach decisions on vaccines? We’ll explore this question more deeply in our next post, but the following thoughts are a start.

The development of vaccines has been one of the great achievements in the history of healthcare. The extent to which they have reduced the burden of disease around the world cannot be overestimated. Christians recognise this as God’s common grace. For many of us, most of the time, receiving a vaccination is a relatively simple action. It is not only protects the individual but is a contribution to public health.

There are important ethical questions to answer about the source of some vaccines and about the rights and freedoms for people to not be vaccinated. The background to thinking about those questions has to be the recognition of the way vaccination works: protecting the vulnerable through the effort of most people in society. Herd immunity allows us to each contribute to the common good.

*The author, Nalini Pather, is a senior academic in medical sciences at the University of NSW. She holds a doctoral degree in cell biology and additional postgraduate qualifications in clinical anatomy, and university learning and teaching. Her areas of research include applied anatomy and medical imaging, medical education and ethics. Nalini serves on the Gospel, Society and Culture committee.

Part 2 in the series click here