LEWIS JONES* considers whether aspects of our socio-cultural formation play a part in the psychological impact of this ongoing Covid crisis.

About two weeks into our COVID-19 timeline in Australia, typically taken as time since the 100th confirmed case, researchers began surveying Australians about mental health. Similar projects were undertaken at the same point in the timeline in China and the results are interesting.

In China, 64-69%, or about two-thirds of participants showed normal levels of anxiety, stress, and depression, while, in Australia, the numbers were 50%, 46%, and 38%, respectively, or only about two-fifth to one half of the population showing normal levels. To put this another way, up to one-third more of our population were showing unhealthy levels of anxiety, stress, and depression at the onset of COVID restrictions and the rapidly increasing COVID infections compared with China. Attempts to explain the differences with various demographic factors, such as student status or self-reported physical health, were unsuccessful. Newby, et al speculate that the difference could be explained through a bias in the sample, though they confess it is unlikely to account for the full difference.

One sample bias that was not considered was that all the people surveyed in China, were, well, in China, and all the people surveyed in Australia were… well, you get the picture. What if a Chinese student has quite a different attitude about or experience of what it means to be a student compared to an Australian? What if a Chinese person thinks quite differently about the nature of physical health and what is good health and bad health compared to an Australian person? That is, is there room to imagine that our individual responses to the ravages and restrictions of COVID-19 are not only internally generated, but also culturally conditioned? If so, could this help us identify the source of not only some of our mental health struggles, but also our general responses to the pandemic that fill our Facebook feeds, e.g. arguments over basic freedoms and mandated vaccinations or religious freedoms and singing in church? Brisbane, Sydney, and Melbourne all experienced lockdown-flouting protests with thousands of people coming out to express their contempt for the way citizens are being treated by government; people shouting “freedom” as they marched toward the CBD in Sydney.

In 1965, Geert Hofstede founded the personnel research department of IBM Europe and from 1967 to 1973 conducted an attitude survey of 117,000 employees across 50 countries. He identified in the data what he classed as four dimensions of national cultural attitudes:

Power Distance

Individualism versus Collectivism

Masculinity versus Femininity

Uncertainty Avoidance

Later research led to the addition of two further dimensions:

Long Term Orientation

Indulgence versus Restraint

The scale ranges from 1 to 100. See the panel at right for descriptions of the dimensions.

While the research has its limitations, e.g. a sample of predominantly male engineers and sales representatives in one of the first global technology corporations, his model of dimensions of culture has proven to be a useful tool for starting conversations about differences in attitudes across cultures.

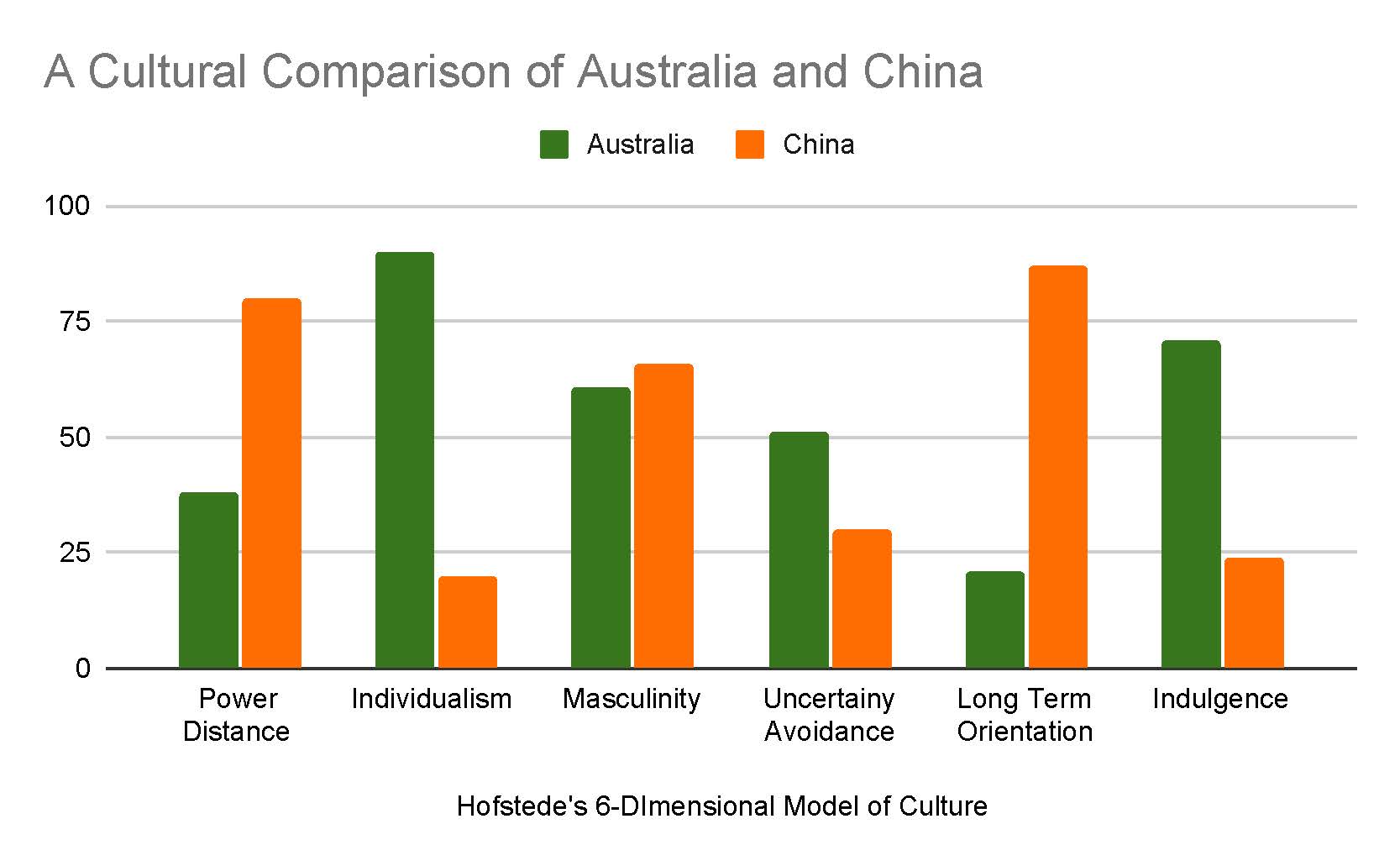

In comparing Hofstede’s 6 dimensions between China and Australia (Figure 1), some fairly obvious differences present themselves. The only truly similar score is in the masculinity dimension which measures the degree to which a culture is oriented toward being the best (classified by Hofstede as masculine) versus liking what you do (classified by Hofstede as feminine). Beyond that, nothing is remotely the same.

Could our different mental health outcomes be related to the relative acceptance of power difference in Chinese culture versus our deep unease with a fellow Australian thinking they can tell us what to do, even if they are the Prime Minister or Premier? Could some of our emotional stress and strain be related to being told the primary orientation of our actions is now the common good rather than the expression of our individual desires?

Australia is an indulgent culture

China scores low on Uncertainty Avoidance and high on Long Term Orientation, which means the Chinese tend to be pragmatic and prepared for change, with a high propensity to save for the future. With our low Long Term Orientation score, Australians look to the past for stability, aren’t concerned about saving for the future, and want quick results from our endeavours. Finally, Australia is an indulgent culture keen to realise our desires and we spend freely to make it happen.

Everyone of these broad cultural differences is a candidate to explain the difference in mental health outcomes between China and Australia. We don’t like authorities telling us what to do. We are not accustomed to constraining ourselves for the good of others. The past is no longer a model for how to act in the present. Our lack of saving means any potential disruption to income verges on catastrophe. Our self-indulgence rubs up against the near complete lack of permitted leisure activities due to travel and gathering restrictions. It would seem we Australians have good reason to be over-stressed relative to our Chinese neighbours, but if those are the reasons, they’re cultural reasons. Without our own research, we can’t tell you whether those reasons do indeed account for the difference in mental health outcomes, but they might help us reflect on our own reactions to the COVID constraints we live with in Australia.

Cultural intelligence starts with the simple recognition that you have a culture; you were raised by a culture. Cultures, however, are like accents. Everyone else has one. It seems obvious to us that the way we speak is not just normal, but normative; it’s right. In the same way, our culture seems both normal and normative. In practice, the normative belief about culture is assumed, rather than argued, because we are not acknowledging the existence of our culture to begin with, which means it can’t be discussed.

‘What gets measured, gets managed’

What is so helpful about Hofstede’s dimensions of culture is that it takes what is tacit and makes it explicit. As the old business adage states, “What gets measured, gets managed.” When we see that our culture can be measured in the same way other cultures can be measured and the measured differences resonate with the way we experience people from another culture, we seem to become more free to discuss our own culture. This is a precious thing because cultures are not neutral and if we are to live well for God in this age then we need to hold up all cultures, including our own, to the exposing light of Christ in the Scripture. Two basic truths about culture can be found in the Scripture that should make us keen cultural analysts.

All cultures are evil in their attempts to find unity, purpose, and security in human traditions and achievements rather than in Christ.

All cultures are good in their recognition of our common createdness and finitude, our need for cooperation and relationships, and our desire to pass on hard-won wisdom and truth to future generations as we seek to fulfill our purpose and exercise a right dominion over God’s creation.

When it comes to COVID considerations, beyond the question of whether broader cultural assumptions are contributing to the degradation of our mental health, we can ask where do our cultural assumptions play into our response to the government vaccination program or public health orders restricting our freedom of movement and association.

Two clear stakes in the ground

The Bible gives us two clear stakes in the ground when it comes to our relationship to government. First, we are called on to honour and submit to the governing authorities for they have been established by God (Romans 13:1-10; 1 Peter 2:13-25). Second, very narrowly, at least, we can say that the government does not have the authority to ban speaking about Jesus (Acts 4:18-20). There is also the principle of conscience (cf. Romans 14, 1 Corinthians 8-10), which acts as a diffuser over these two simple principles, but that is beyond our scope here. My aspirations are far more modest. Let’s simply use our new found cultural insights to reflect on our responses to COVID-related government interventions.

Are you cynical about the daily briefing from Gladys? Are you inclined to mock the Premier and Dr. Chant and Minister Hazzard as they call on us to tell the truth to contact tracers or just do the right thing? Do you question the right of the government to keep you from visiting a dying relative or attending their funeral? To what degree is your cynicism a product of being raised in low Power Distance Index Australia where one of our bedrock beliefs is that unequally distributed power is wrong. To what degree are we baptising a flat democracy when the gospel we preach is all about the absolute monarchy of God and the New Testament authors weren’t even close to advocating the overthrow of their contemporary authoritarian regimes?

Important questions

Are you angry about the idea that you are being called on to get vaccinated for the sake of herd immunity when you don’t think anyone should be required to get vaccinated at all? Are you inclined to let others get vaccinated to get us over the right percentage to keep the community safe and not do it yourself? To what degree might your anger stem from Australia’s highly individualistic culture when Jesus says that half of the greatest commandment is to love your neighbour as yourself?

Are you indignant about being told you cannot go to a friend’s house or gather with extended family for a birthday or go out to get your morning coffee at your favourite cafe? To what degree could your indignation stem from the sense that restraint is bad because it keeps you from being you and that living your chosen lifestyle is your birthright as a high Indulgence Index Australian?

These are not accusations. These are genuine questions flowing out of the broad generalisations of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and the measurements of those dimensions in Australia. They are culture-wide generalisations. They are not about any given individual, including you! The point of this exercise is to recognise the generalisations and reflect on your own motivations in light of them, so that we can all see the contingent, rather than normative, nature of culture, sit loosely to it in light of Scripture, and depressurise discussion and debate around COVID and various government interventions. Indeed, some of our cultural assumptions will have been handed down to us from western Christendom, but to leave any assumption unexamined leaves us prone to blind spots.

Our government has yet to ban us from speaking about Jesus, so let’s keep busy about those things the apostles considered essential and not get too flustered about the rest. Perhaps we can use our cultural ruminations to ask our friends from other cultures about things that are important to them. You may even get the chance to explain how the death and resurrection of Jesus relativises culture and grants you eternal citizenship in heaven.

* Lewis Jones is a member of the Gospel, Society and Culture committee. He ministers on university campuses with AFES, leading the Simeon Network, a network of Christians working in academia. He holds a PhD in astrophysics and a degree in theology from Moore Theological College. He is married to Jenny, has three children, and is a member of Randwick Presbyterian Church.

Hofstede’s 6 Dimensions of Culture

POWER DISTANCE

This dimension deals with the fact that all individuals in societies are not equal – it expresses the attitude of the culture towards these inequalities amongst us. Power Distance is defined as the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organisations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally. It has to do with the fact that a society’s inequality is endorsed by the followers as much as by the leaders.

INDIVIDUALISM

The fundamental issue addressed by this dimension is the degree of interdependence a society maintains among its members. It has to do with whether people´s self-image is defined in terms of “I” or “We”. In Individualist societies people are supposed to look after themselves and their direct family only. In Collectivist societies people belong to ‘in groups’ that take care of them in exchange for loyalty.

MASCULINITY

A high score (Masculine) on this dimension indicates that the society will be driven by competition, achievement and success, with success being defined by the “winner” or “best-in-the-field.” This value system starts in school and continues throughout one’s life – both in work and leisure pursuits.

A low score (Feminine) on the dimension means that the dominant values in society are caring for others and quality of life. A Feminine society is one where quality of life is the sign of success and standing out from the crowd is not admirable. The fundamental issue here is what motivates people, wanting to be the best (Masculine) or liking what you do (Feminine).

UNCERTAINTY AVOIDANCE

The dimension Uncertainty Avoidance has to do with the way that a society deals with the fact that the future can never be known: should we try to control the future or just let it happen? This ambiguity brings with it anxiety and different cultures have learnt to deal with this anxiety in different ways. The extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations and have created beliefs and institutions that try to avoid these is reflected in the score on Uncertainty Avoidance.

LONG TERM ORIENTATION

This dimension describes how every society has to maintain some links with its own past while dealing with the challenges of the present and future, and societies prioritise these two existential goals differently. Normative societies, which score low on this dimension, for example, prefer to maintain time-honoured traditions and norms while viewing societal change with suspicion. Those with a culture which scores high, on the other hand, take a more pragmatic approach: they encourage thrift and efforts in modern education as a way to prepare for the future.

INDULGENCE

One challenge that confronts humanity, now and in the past, is the degree to which small children are socialized. Without socialization we do not become “human”. This dimension is defined as the extent to which people try to control their desires and impulses, based on the way they were raised. Relatively weak control is called “Indulgence” and relatively strong control is called “Restraint”. Cultures can, therefore, be described as Indulgent or Restrained.

Sydney CBD Peak Hour: Photo: Dion Christophoratos