A quick end to Covid is wishful thinking. But pandemics can also be catalysts to rebuild societies in new and creative ways, writes NALINI PATHER*.

With the increased uptake of vaccines, as well as discussions about the road out of lockdowns and even vaccine certificates and passports (a discussion of its own), we might begin to think that the end of COVID is in sight. This is wishful thinking.

COVID and its impacts will be with us for a long time, perhaps well into the next decade. In all likelihood, infections will never come down to zero in the near future but they will come down to a level that we find more acceptable and that can be managed by health services. Pandemics though are as much social and economic problems as they are a health problem. But pandemics can also be catalysts to rebuild societies in new and creative ways.

Some of the issues that stress us most now, like not being able to attend church, visit family, go on holiday or even go to the hairdressers, will ease as more people are vaccinated and we emerge from this lockdown. But there are deeper impacts of this disease that affect our wellbeing, both as individuals and as a community. This pandemic has exposed hidden disparities, exaggerated existing inequalities and created new challenges. The more we understand the present circumstances and our vulnerabilities, the better we can address the issues that face us – even amid uncertainty.

Ecclesiastes 3 reminds us that there is a time for everything (v1). God, who is in control of all things, will make everything beautiful in its time (v11). “Everything God does will endure forever” (v14). We do not have His eternal perspective; we “cannot fathom what God has done from the beginning to end” (v11). So, on the one hand, we have to discern what is ‘beautiful’ for this time so that we can faithfully advance God’s purposes for God’s world. Yet, we do this with humility, acknowledging our limits. That is what it means for us to ‘revere’ Him (v14).

So, with this reminder from the passage that there is a time for everything in this complex world and that the only thing we can be certain of is that God reigns, let’s reflect on our current time and place and perhaps even consider the best, most ‘beautiful’ response to the ongoing crisis of this pandemic.

Long COVID

From a health perspective, the virus will be with us for a long while still; there is much that is uncertain. Even for those who have had the disease, their challenges are not over when they recover. A significant number of people, even those who had a mild form of disease, continue to experience symptoms long after their recovery. This is described as the post-COVID-19 syndrome, post-acute COVID, chronic COVID or “long COVID”.

The cause and risk factors of long COVID are not clear as the syndrome has only recently become evident. It seems to be twice as common in women, and seems to affect even people who have few or no symptoms during their infection. Some people consider that long COVID may be due to an overreaction of the immune system, while others think it may be due to virus fragments that remain in the body, like the Epstein Barr virus in the case of glandular fever. However, there are no real answers yet.

Long COVID can persist for more than three months after recovery from the infection. Recent studies showed that this was true for approximately 5–25% of people with COVID-19. Symptoms include: fatigue, shortness of breath, heart palpitations, chest tightness and pain, loss or change to smell, head and joint pain, memory loss, concentration issues, depression and anxiety. This wide range of symptoms is likely to be due to the multiple organs in the body that the virus affects.

With relation to mental health, it is also important to remember that simply surviving COVID-19 can make a person more likely to later develop post-traumatic stress syndrome, depression, and anxiety. This effect could be related to lingering concerns about health, periods of isolation and stress about related issues such as work and finances. The long-term health consequences of COVID-19, however, are not known and studies only started recently. This itself creates uncertainty and may mean that we need to adjust our response constantly as new information is available.

Children

One study from the UK for example, demonstrated changes in the brain scans of people before and after COVID. These include loss of grey matter in areas related to memory such as processing of events, familiarity of objects, and smell and taste. This is part of the concern with the increased number of infections in younger people and children – groups in which the brain is in important stages of development. Studies from other countries are not clear on the effect of COVID on children – and why long COVID affects some more than others. These are issues to consider as the proportion of young people and children with COVID increases, and as debates on the benefits of vaccinating children become more relevant.

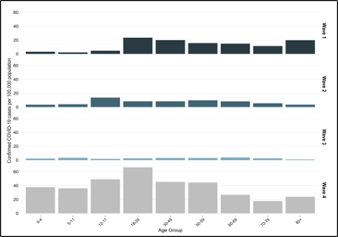

Emerging from this lockdown before vaccination is available for children makes a significant number of health professionals uneasy, some even calling this out as an inequity that will be our undoing in the months ahead. There is, however, acknowledgement that we need to understand better the risk versus benefit for children. In this current NSW delta wave, similar to other countries, children carry the highest caseload and have the lowest vaccination rate. Children are overrepresented in the case numbers relative to their population size; aged 12-17 years represent 49.2% per 100 000 people infected (see figure 1).

This is not very surprising since this group is mostly unvaccinated. While the outcome for most in this group who do get infected is expected to be good, and notwithstanding that there are significant numbers with existing health issues, there remains uncertainty of the full impact of COVID on this group. The announcement that vaccines will be available for children 12 years and older on Friday 27 August 2021 was greeted with a sigh of relief to many, although vaccine supply remains an issue. We need to understand better how the hardships associated with the pandemic have impacted children. For this we need to weigh the impact on their social and relational health, learning, and even Christian life and discipleship. We need to also weigh the benefit of vaccinating this group when other more vulnerable people have not yet had access to the vaccine.

Figure 1. NSW rates of COVID-19 infection by age group for the four waves of the pandemic from 25 January 2020 to 31 July 2021. In wave 1, higher numbers of infection were seen in older people. In wave 2 and 3, NSW did not have as much infection and when present were in the more mobile groups and outbreaks at aged-care centres. In wave 4, most infections are in the 18-29 year group, followed by the 12-17year group. Adults who are mobile and work away from home also have high infection. (Source: NSW Health)

The way to manage this pandemic is to make the virus “endemic”. That means that we will be able to live with this virus like we do with the four main viruses that cause influenza. But endemicity is not going back to pre-covid normal. It will be years before we can go back to life the way it was in 2019, if ever. Masks, vaccine boosters and action to increase ventilation indoors will remain for some time. The path to endemicity will depend on how the virus mutates. With so much of the world still unvaccinated, new variants remain a threat, especially if they are capable of infiltrating our defences.

All these health issues do not exist in isolation. There are many interrelated factors that require balance in determining relative risk – both to a person individually and to communities, as a whole. Consider for example, the disparate economic impact of the lockdown on people’s income and employment opportunities, or on physical safety if you are in an abusive relationship. These are significant things we need to be mindful of as we prepare ourselves to exit from lockdowns.

Health Equity

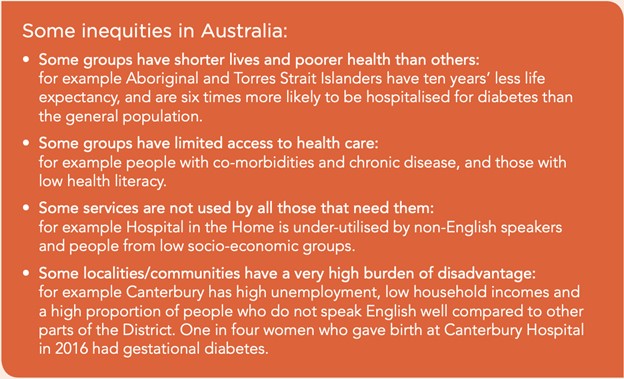

From the perspective of the community, COVID has an unequal impact depending on where we live. Health equity means that ‘everyone has a fair opportunity to enjoy good health and to access the health services they need. Inequities arise when there are systematic differences in health status, health risks or access to health care between groups that are avoidable and unfair’ (Sydney Local Health District, SLHD, Equity Framework).

Irrespective of this definition, God is concerned about the weak and vulnerable. Psalm 68, verse 5 reminds us that God is “Father to the fatherless, defender of the widows – this is God, whose dwelling is holy”. Health equity is not about health only. Health inequalities are related to what we call social determinants of health, i.e. social disparity. The World Health Organisation (WHO) describes social determinants as “the circumstances in which people grow, live, work, and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness. The conditions in which people live and die are, in turn, shaped by political, social, and economic forces” (CSDH, 2008). These are things like housing, education, income, health literacy and social connectedness.

A study in 2019, for example, found that in NSW rural communities, children’s psychological wellness is statistically significantly lower than the Australian norms and is due to personal and family factors rather than the rural locality. Much of the long-term impacts of COVID will exaggerate issues present in our communities and society even before the pandemic (see figures 2 and 3, below). In some ways, support during 2020 like JobKeeper, delayed us from realising the impact on people.

Figure 1. NSW rates of COVID-19 infection by age group for the four waves of the pandemic from 25 January 2020 to 31 July 2021. In wave 1, higher numbers of infection were seen in older people. In wave 2 and 3, NSW did not have as much infection and when present were in the more mobile groups and outbreaks at aged-care centres. In wave 4, most infections are in the 18-29 year group, followed by the 12-17year group. Adults who are mobile and work away from home also have high infection. (Source: NSW Health)

Inequity is present in our city, in our state and is the reason for differences in how the pandemic will impact us both individually and in our local communities. Sometimes we can be guilty of focusing our compassion on geographically distant places and remaining indifferent to those nearer to us. We expect that differences exist in our community but when those differences result in significant negative consequences to the wellbeing of particular groups of people, then it should be of concern to all of us.

This disparity is entrenched in how we live and work, who we socialise with and where we worship. It is often invisible to us but real. Let’s take a deeper look at Sydney as an example, a city of extremes. In 2018, Australia’s death rate decreased on the whole. In places like Pymble and Crow’s Nest fewer than 3 in 1000 people died while more than 9 in 1000 people died in Rooty Hill to Minchinbury; this is also higher than for NSW remote areas (controlling for age).

The reasons for this are complex. It can be as basic as the kinds of foods readily available at the shops near you. Where you live, for example, shapes things like how easy it is to buy healthy food; there are more fast food, sweet and cake shops in the lower income western suburbs, where there is 2-3 times higher prevalence of diabetes, than the north and eastern suburbs.

During the first wave of this pandemic, a report on Australia’s economic well being indicated that in Sydney, for example, knowledge-based industries, like finance and professional services, adapted very well to remote working and experienced less disruption. Service-sector industries like construction, retail, transport and food services suffered significant financial loss. People in knowledge-based industries cluster in specific geographic areas and results in suburbs with economic, education, health and social benefits. The consequences of the pandemic are therefore disproportionate for people in south-west Sydney (SWS) where housing density is higher, for example, than for those in the knowledge-based residential clusters.

At the start of the vaccination rollout, rates of vaccination were significantly better in higher income suburbs, until the massive injection of vaccines into the LGA hotspots. Even with this focused effort, the rate of vaccination remains higher in the ‘knowledge-based’ suburbs. At present, these are also the suburbs with fewer cases of COVID,and less need to travel to remain employed. Those with greater long term economic risk from COVID are more severely affected and in many cases have less influence on power structures in society.

Understandably, the vaccine rollout is unequally distributed between metropolitan and regional areas. For example, on 27 August 2021, NSW Health announced the opening of a drive-through vaccination clinic at Dubbo Showground, expected initially to be able to deliver upward of 200 vaccinations each day. While this is good, considering that there were 42 new cases in that LHD on the day of the announcement, it is not nearly enough to vaccinate the estimated 54,000 people in that area.

This disparity is interrelated and has a wide ripple effect; impacting not only employment and income but also education, health, housing and even public participation. Understanding this flow of impact is important because it helps non-profit organisations and governments anticipate the needs of communities and make better decisions on where and what to invest for maximum impact.

Figure 3. Summary of challenges to health equity among Sydney LHDs. (Extracted from Sydney LHD Equity Framework)

One area in NSW that has been under stress since the pandemic started is housing and homelessness services, especially emergency housing. This is a concern for people both in cities and in regional areas, especially areas that are a major transport hub, like Nowra, Wagga and Dubbo. Housing and homelessness are directly linked to economic and employment challenges. Homelessness even before the fourth wave of the pandemic was predicted to increase by 24% in June 2021, with the largest increases in Hunter Valley, Newcastle and Lake Macquarie – with City and Inner South – areas already recording higher levels of homelessness.

In the housing sector, last year 57% of organisations in NSW reported an increase in clients seeking help to sustain tenancy or prevent tenancy failure or eviction; the largest increase was in the City and Inner South Sydney. Housing stress can lead to overcrowding. While there is not much data that analyses overcrowded housing and health, the pandemic has highlighted the health risk with respect to the spread of infectious disease.

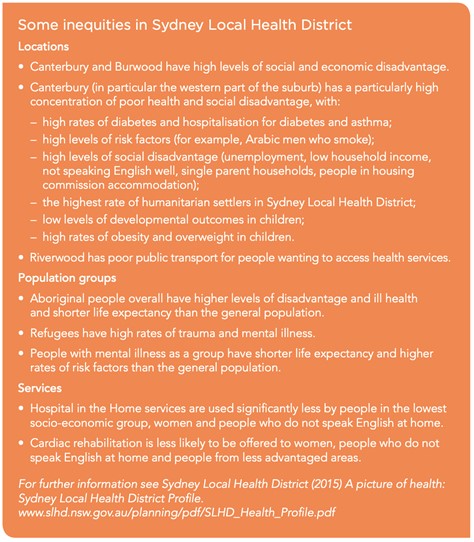

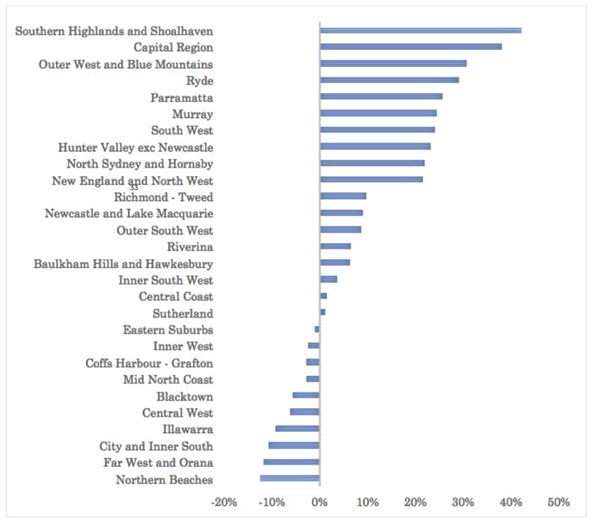

Domestic and family violence, of which there is a marked increase during the pandemic (see figure 4, below), also leads to the demand for homeless services. In NSW, there are approximately 2,500 reports of domestic violence each month, which is estimated to be only 40% of the actual number due to under reporting. The report comparison for the same period in 2019 and 2020 are alarming for some suburbs (see figure 5, below).

Figure 4. Trends in reported incidence of domestic and sexual assault (extracted from NSW Recorded Crime March 2021 Report). Sexual assaults involving victims aged 13-to-20 years accounted for two thirds of the increase and the vast majority involved female victims. The rise in sexual assault reports was as much to do with an increase in recent contemporary assaults as it was related to reports of historical offences.

The Australian Institute of Criminology survey of 15,000 Australians in May 2020 reported a large increase in women reporting abuse for the first time and also reporting an increase in abuse. One theoretical model used to understand the link between economic stress and domestic violence is the “intra-household bargaining model”. By this model, an increase in male unemployment or a decrease in female unemployment reduces violence against women, i.e. when the gender-wage gap decreases. This is not easy to understand and is multifaceted but lends to the uncertainty at our doorsteps.

Figure 5: Change in domestic violence reports to police: May-June 2019 vs May-June 2020 (Source: NSW Equity Report) The bars on the right of the vertical line indicate the percent increase in cases while the bars on the left indicate a decrease. Southern Highlands and Shoalhaven experienced the greatest percentage increase while Sutherland the least. Eastern Suburbs to Northern Beaches experienced decreases in percentage of cases with the the greatest percentage decrease in Northern Beaches.

Another area of concern at present is child violence. During lockdowns, the usual structures that monitor harm to children, such as schools, extended family and neighbours etc., are disrupted. In the UK for example, one hospital reported a 1,400% increase in abusive head trauma during the lockdown. In NSW, areas such as Newcastle and Lake Macquarie, Hunter Valley, Sydney Outer West and Blue Mountains have higher levels of children at risk of serious harm than the State average.

Towards a ‘beautiful’ response for our time

The Lord has appointed this time and place for each of us. So, with information such as that discussed in this article, how might we make small, tentative steps towards a “beautiful” response in this present time?

First and foremost, this is an opportunity for us to remember that God is in charge and we are not. Ecclesiastes 3 reminds us that it is God, not us, who makes things beautiful in His time (v11). Our best response is to revere Him (v14). Christ’s resurrection gives us confidence to worship, to revere, God. Life in this world, while good, is not ultimate. Ultimate life is to be with the risen Christ in a new creation.

We are reminded too that real hope, even in a pandemic, lies in people hearing the good news, “I tell you the truth, whoever hears my word and believes Him who sent me has eternal life” (John 5:25). This is our assurance in the face of uncertainty and hardships.

Do not underestimate the power of the gospel. Many of us may have been Christian for many decades, perhaps our whole life. For us, it’s the old, old story of Jesus and his love. But in today’s secularised society the idea that we are not in charge, that we don’t have all the solutions to defeat this virus, can be confronting and perhaps even demoralising. But for the same reasons, the idea that there is a good God, who offers us a life not limited by this world, therefore invulnerable to things that plague this world – “eternal” life, resurrected life with the risen Jesus – can be unexpectedly attractive. “Thanks be to God”, who “gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Cor 15:57).

That said, don’t underestimate the power of simple but creative ways of sharing this gospel hope. Augustine echoes Ecclesiastes 3’s observation that God has put eternity in our hearts in his famous dictum: “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it rests in you”. We can have joy in uncertainty and suffering because our satisfaction is founded not in this world, but in the eternal resources and eternal life of the risen, almighty Jesus Christ.

It is a joy that we cannot help but want to share, as illustrated in the life of Arthur Stace, Sydney’s Mr Eternity (if you are looking for something to read, it is intriguing). Stace had an impoverished childhood in Redfern, served in WWI but was discharged as medically unfit. He struggled with alcohol dependency afterwards. After hearing a sermon in 1932 by Rev John Ridley on ‘The Echoes of Eternity’ that spoke to his need, he took to writing the word ‘Eternity’ across the city for the next 34 years, estimated to be more than half a million times, for which he is famously remembered.

Figure 6. Mr Eternity. The Sun-Herald, Sunday 1 November 1953 (retrieved from Trove)

A reflection on the community, city and State in which we live can give us perspective of how we can “revere” God by preparing for the future and by loving those he cares about (James 1:27). Ultimately, loving them so that they may meet Jesus who said “I assure you: Anyone who hears My word and believes Him who sent Me has eternal life”. (John 5:45). And against our backdrop of suffering, eternity will shine brighter still.

*The writer, Nalini Pather, is a senior academic in medical sciences at the University of NSW. She holds a doctoral degree in cell biology and additional postgraduate qualifications in clinical anatomy, and university learning and teaching. Nalini serves on the Gospel, Society and Culture committee. She is married to Glen and they serve in ministry at Rose Bay Presbyterian Church.

Photo by Valiphotos

from Pexels