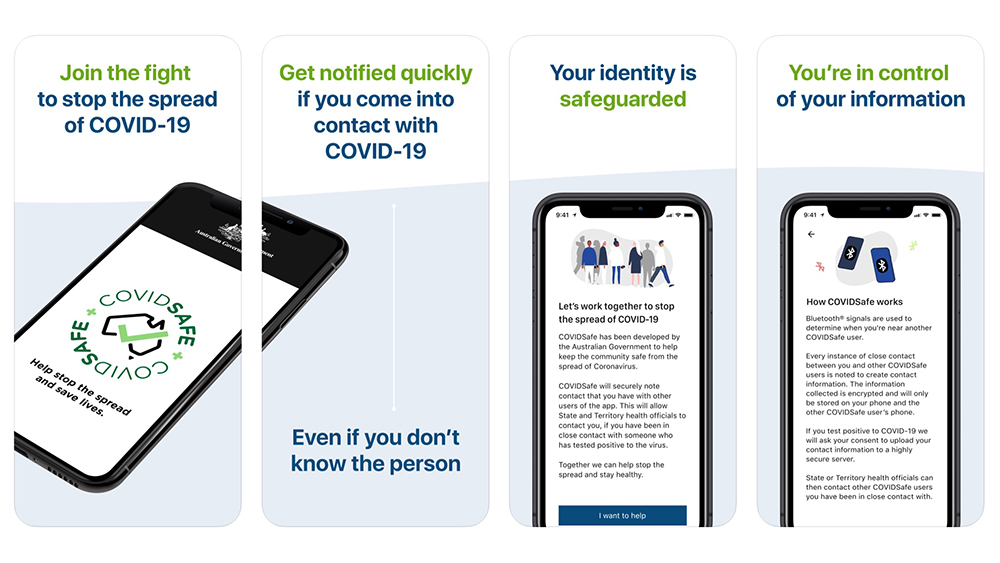

On April 26th, the Australian Federal Government released COVIDSafe, a contact tracing App for smart phones. The App aims to help State and Territory health officials trace the contacts of people who test positive for COVID-19. It won’t replace the current manual process of contact tracing, but will supplement it and speed it up. The Health Department’s explanation of how the App works can be found here: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/Apps-and-tools/covidsafe-App.

A summary of how the COVIDSafe App works

- Use of the App is voluntary. Consent is required at each stage of the registration process, and also if information is transferred to health department data storage systems.

- When users install the App, the initial information stored is the user’s name (which could be a pseudonym), their phone number (which is verified via SMS), their post code and their age range (in 10 year brackets). A unique encrypted reference code is then created a by the system for the phone on which the App is installed.

- COVIDSafe recognises other devices on which the App is installed and Bluetooth has been enabled. When the App recognises another user who is 1.5 m away for a period of 15 minutes, it notes the date, time, distance and duration of the contact and the other user’s reference code. The App does not collect information about the location at where the contact was made.

- The information collected is encrypted and the encrypted identifier is stored securely on the phone. Contact information will be deleted from the App on a 21-day rolling cycle.

- Users who receive a positive diagnosis of COVID-19 will be asked by health officials in their State or Territory to allow the encrypted contact information from the App to be uploaded to a highly secure information storage system.

- The data will be stored in Australia. Users cannot access the information themselves, nor can anyone other than an authorised health official.

- Information on the health departments’ storage systems will be used to trace contacts so they can be given information about how to seek medical advice. The name of the person with the positive diagnosis will not be given to contacts.

- At the end of the pandemic, information on the storage systems will be destroyed.

- Users can delete the App (and the information it has collected) from their phone at any time. All users will be asked to delete the App from their phone at the end of the pandemic.

The App does not collect information about the location at where the contact was made.

What about technical limitations and privacy?

There are some limitations to the App.

- Mobile contact tracing tools will not cover people who don’t have smart phones – this includes many young children, and a significant proportion (45%) of people over 55 years of age.[1]

- It may not function on older smart phones, and will not function on non-smart phones.

- Bluetooth connection may not be reliable in some circumstances (giving either false negatives of false positives about ‘contact’).

- Phones must be turned on, Bluetooth enabled and the App open – this may have an impact on battery life. Battery-saving features may flag the App as causing excessive power consumption.[2]

Legitimate concerns have been raised by privacy advocates and information technology experts. The Federal Department of Health commissioned a Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) which was released on April 24th, two days before the App became available. The PIA can be downloaded here:

https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/covidsafe-Application-privacy-impact-assessment.

The report recognises that “the importance placed on privacy has facilitated the adoption of a “privacy by design” Approach, with decisions being made to change the design of the App to mitigate against identified privacy risks during this PIA process” (p 4).

Several recommendations were made about further work that should be done to deal with privacy concerns. It’s fair to say that in the release version of the App, these recommendations have received attention.

A number of experts have assessed the App (by decompiling the code) and have declared it to be transparent and successful in meeting industry standards.

The Australian Information Industry Association (AIIA), for example, has indicated its strong support for the App: “… on this detailed briefing [from the Federal Government] and understanding that the App does not track your geo-location and that personal data and cyber security concerns have been designed into the App, the AIIA therefore supports the government tracing App and strongly recommends that all Australians download it … In the absence of a medical vaccine, you could think about contact tracing as a digital vaccine with our contact data being the virtual antibodies.”[3]

[1] Rachel Coldicutt writing for The Medium, 23 March 2020. Rachel’s open letter (co-signed by several other digital technologists) focussed on the development of an App for the NHS in the United Kingdom.

[2] https://www.techguide.com.au/news/mobiles-news/covid-safe-App-downloaded-million-times-lives-privacy-promise/

[3] https://www.startupdaily.net/2020/04/mike-cannon-brookes-paul-bassat-covidsafe-App-tech-sector/

The report recognises that “the importance placed on privacy …”

Privacy and the Common Good

Even apart from such assurances, there are good moral and ethical reasons for considering use of the App. The Australian Government is promoting its use as a means of finding and containing outbreaks of the pandemic, so that Australians can be protected and social distancing restrictions eased.

A purely utilitarian approach would suggest that if great good can be achieved, then some trade-off in privacy might be reasonable. Further, it’s been recognised that social distancing, though applied equally to individuals, has an unequal impact: people with job security experience isolation and inconvenience, but those without work or paid sick leave or savings experience significant hardship. It’s argued that digital contact tracing “could offer geographically targeted, appropriately scoped quarantines that minimize additional hardships for society’s most vulnerable communities.”[1]

Christians might also consider what the Bible says, and doesn’t say, about personal privacy.

On the one hand, the Bible affirms privacy. There is privacy out of a concern for modesty: exposing someone’s nakedness is wrong (Gen 9); women’s privacy during menstruation is respected (Gen 31); certain hygiene practices are carried out in private (1 Sam 24). There is privacy connected with piety: fasting in private (Matt 6); alms-giving done in private (Matt 6); private prayer is contrasted with proud public prayer (Matt 6). And even though there’s an assumption of close-quarters living in the Bible[2], there are limits to what may be made public: gossip and slander is prohibited (Lev 19; Prov 11; Prov 25); and the home seems to be regarded as a private domain (lenders are instructed to wait outside to collect a pledge offered by a borrower, Deut 24).

On the other hand, the Bible affirms openness. We see openness for the sake of gospel witness: Christians should shine as a light in the world (Matt 5); and Christian character should be observable in public (1 Tim 3 – the character of elders is on show). We see openness for the sake of piety: sins should be confessed to one another, not held privately in the heart (James 5); and deeds done in darkness are to be exposed (1 Cor 5) because “privacy allows people to do things that displease the Lord.” [3] And we see openness for the sake of others: the commands to bear one another’s burdens assume a level of openness that would make those burdens known to (at least some) others.

One survey of how the Biblical narrative deals with the question of privacy concluded that “the common moral lesson is that the individual deserves to be protected from public encroachment into the personal domain … and as a counterpoint to this expectation, there exists an obligation for every individual and organization to respect other individuals’ privacy.”[4] The Bible seems to “prioritize privacy rights at an intermediate level between civil and criminal rights. Where information has economic value, then privacy takes precedence over economic usefulness. Only where there is an immediate threat to life is the right to privacy superseded.”[5]

In an age where we share so much of our personal information with others, especially digitally through social media and smart phone Apps, it’s right to be concerned about how that information is stored, who accesses it, and for what purpose.

How much of our personal information might we be willing to share for the benefit of others? How much liberty might we give up for the common good? How much common good would an action have to achieve in order for us to give up that liberty? Is it possible that giving up some liberties (such as having no one know who you stood beside at the butcher’s) might lead to reclaiming others (such as the freedom to congregate in public)? These are valid questions to which each of us needs to find an answer.

The current context of a discussion about privacy and the common good – in the midst of a pandemic where no vaccine yet exists for the disease – leads us to different conclusions than we might have reached even 4 months ago. More is at stake here than in our society’s other debates about government surveillance, digital marketing strategies and the use of personal information by corporations for their own gain. In the current context, is it perverse to say, on the one hand, that we – Christians – are a people who are not anxious or fearful, and then on the other to express distrust of a tool offered for our protection by a government that is accountable to us and has not deliberately harmed us? Do we doubt God’s sovereignty?

COVIDSafe has much to offer as a tool for helping Australians navigate the path out of this pandemic. Its use should be widely encouraged, for the sake of loving our neighbours and bearing one another’s burdens.

This blog, researched and written by Ben Grieg and Sheryl Sarkoezy, is endorsed by the Gospel, Society and Culture committee.

[1] http://blog.practicalethics.ox.ac.uk/2020/04/guest-post-pandemic-ethics-social-justice-demands-mass-surveillance-social-distancing-contact-tracing-and-covid-19/

[2] Mark Roberts, “Privacy and God”, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/markdroberts/series/privacy-and-god/

[3] Mark Roberts

[4] Benjamin Glass and E. Susanna Cahn, “Privacy Ethics in Biblical Literature”, Journal of Religion and Business Ethics, April 2017, p18

[5] Glass and Cahn, p21

How much of our personal information might we be willing to share for the benefit of others?