Our world is working out how to respond to the COVID-19 crisis. As we restrict our contact with one another, in order to stop the spread of the virus, what does it mean for Christians to seek the “common good” in our world? Our Committee Convener, John McClean, reflects on this, and offers some thoughts that we trust will encourage and challenge you in the days ahead.

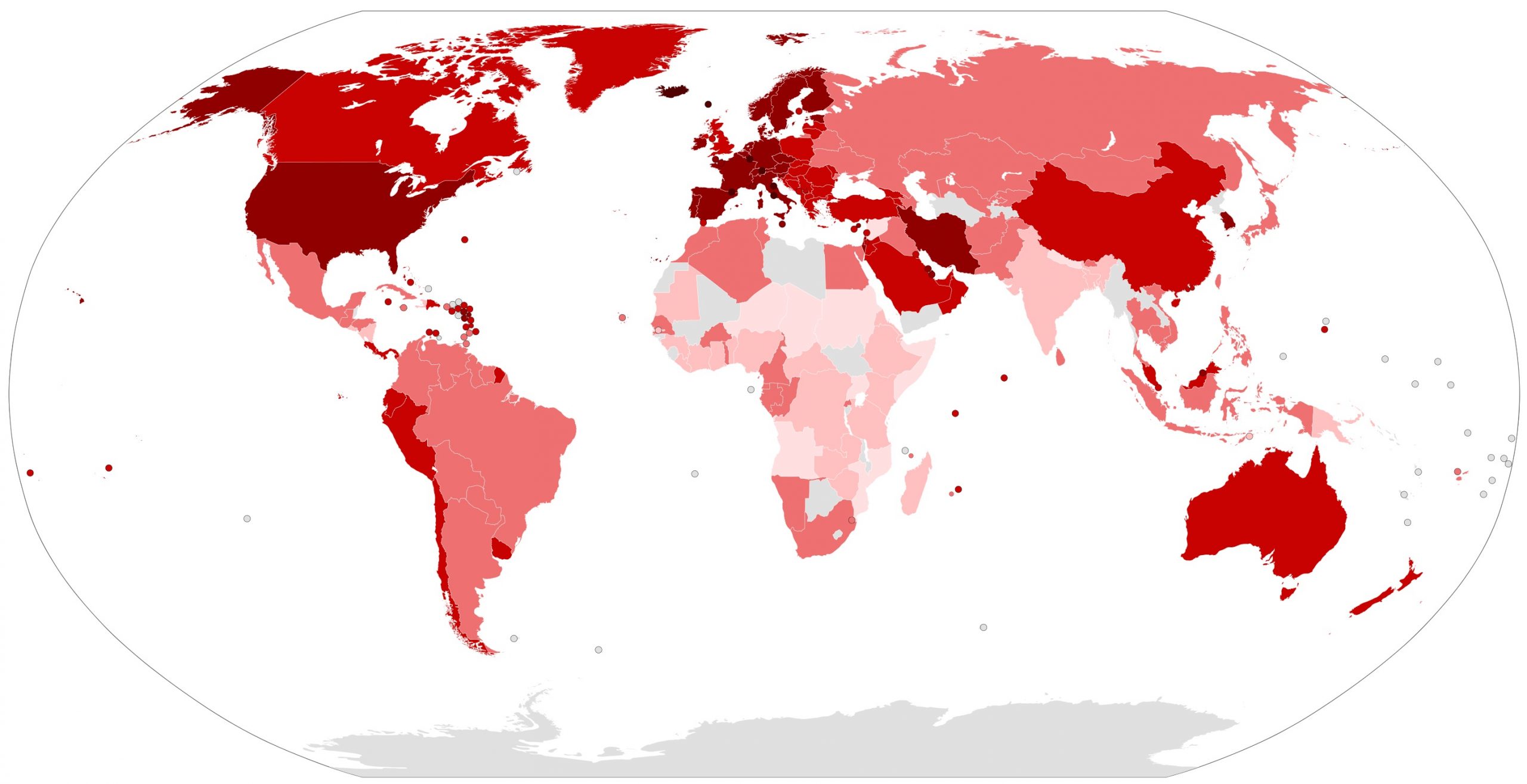

We are facing a virus crisis. Perhaps it is not unprecedented, there have been other pandemics with huge death tolls. Yet the world is also more connected than ever before, and more integrated economically. The result is that the infection and its impacts spread faster than ever. These factors may make the whole event unprecedented.

There are a host of ways in which the gospel of Jesus addresses our situation and gives hope and direction. Here I want to pick up one important theme — the idea of the “common good”. The virus and its impact show us the existence of the common good and underscore why we need to be committed to it.

COVID attacks the common good

Our crises reveal how highly connected to and dependent we are on one another. In our individualist consumeristic culture, we easily imagine that almost everything in life is available, at a cost, to suit our preferences. What our neighbour wants or needs seems relatively independent of our own options. Again, that’s a myth. In fact, we are highly dependent on each other.

The threat of coronavirus shows our interconnections. It spreads because we spend time together and are connected across cities and nations. At the same time we need help from each other. A huge network is involved in responding: cleaners, paramedics, delivery drivers, medicos, corporations, researchers and more.

The economic effects of the pandemic also reveal our connection. As China struggled, other economies suffered. Now, as the pandemic rolls around the globe, interruptions to travel and trade have sent the global economy into a tailspin. No doubt there are weaknesses in the global economic structure, and perhaps it is too dependent on a few major economies. Even if we restructured the world economy, human prosperity would still depend on our multiple connections and mutual interests.

At the local level each café that closes and every cancelled concert means less money is spent on clothing or cars. So, the effects ripple through the community. Economics is not a zero-sum game. Often prosperity for one funds that for others. Of course, it is far from a perfect rule, and there are many times when the rich prosper at the cost of the poor. That is also evidence of our connections.

The economy reflects deeper links. Our lives are woven on the warp and woof of social connections. Our families, friendships and communities make us who we are. These in turn depend on wider networks with billions of people we do not know personally, each in their own web of relationships. Like economics, our shared good can expand as it is shared.

These shared realities of life form the “common good”. This not simply what is good for most people. The default view of liberal democracy is that the majority preference is the best, but the common good is more than the sum total of these preferences. It is concerned with a common life shared by all members of a society in which everyone has an interest and minorities are included. Roads, sports grounds and the local shops (stocked with toilet paper) are material elements of the common good. The legal system is also a part, as are shared culture, symbols and activities.

The gospel and the common good

The common good is a profoundly Christian idea. Adam and Eve were set in the world to fill it, and from them was meant to develop a human community with a godly culture. God made us to live together, not apart. From the very beginning, humans gathered in families and in cities (Gen 4:17). Human sin corrupted our shared life and the divisions of humanity — reflected in broken families, communitarian violence and war — are the awful consequences of sin (Gen 11; Tit 3:3; James 4:1). God’s response was to call Abram and promise to make his descendants into a great nation (Gen 12:2-3), to redeem that nation from Egypt and to establish them in the land to live as a people, not simply as individuals. The pattern of Israel is re-established in the church through Christ. The body metaphor of the New Testament underlines how connected we are to Christ, as head, and to each other. We know God together, we grow together and suffer together (Rom. 12:4; 1 Cor. 12:12–20, 22, 24–25, 27; Gal. 6:17; Eph. 1:23; 2:16; 3:6; 4:4, 12, 15–16, 25; 5:23; Col. 1:18, 24; 2:19). God’s final purpose is to have his people, gathered from all nations, living in unity in fellowship with him (Rev. 21:3, 9–21).

All of that means that God is committed to community and we are made for it. Families, neighbourhoods, cities, nations and the whole human race are not the church; but the church is the foretaste of God’s kingdom. With that perspective we recognise that we live together — the real goods in life are common goods.

Church is, at least, the foretaste and sign of the city of God. It reflects the way God has made people to live. On that basis, we should be concerned about the “secular” common good, as well as the church. (For more on this see Jake Meador, In Search of the Common Good : Christian Fidelity in a Fractured World IVP, 2019, which I have reviewed here.

The current medical crisis underlines the importance of the common good. As various events are cancelled and institutions closed, there is a loss to our shared life. Eurovision Song Contest has just been cancelled. I was not planning to watch a moment of it, but I’m saddened by the announcement. Multiply it thousands of times and we are all the poorer.

The crisis challenges us to pursue the common good. Through the bushfires, Australians showed some real commitment to this. The RFS were the heroes of the summer because they represented ordinary Australians working for the whole community in their own time and at their own cost. (Well-meant calls to pay the RFS missed that).

In contrast, panic buying and hoarding seem to be all about individual (and family) survival — or comfort — with no apparent concern for the impacts on others. Empty shelves in the supermarkets are a telling example of the way a series of relatively small personal actions accumulate to undermine the common good.

Following guidelines to reduce the spread of infection — hygiene directions or limitations on activities — is also about the common good. You’ve probably heard people say, “I don’t need to worry, since I am young and healthy I’ll be fine”. The common good perspective is that to limit the burden on health services, each of us needs to make adjustments. The cost may seem out of proportion of the risk which the virus poses to you. The question is not how to manage your own personal risk, but behaviour which contributes to shared good. For a Christian, personal convenience is not top priority (Phil 2:4). Every time you wash your hands, you are not simply protecting yourself, family and friends — it’s care for each of us and all of us together.

COVID-19 challenges our commitment to global community. The problem does not end at our borders (as we know too well). Halting international travel will probably help the global situation, but it should not mean that we forget our international neighbours. Institutions such as the World Bank and World Health Organisation have taken some action to help developing nations. Given our readiness to cut our aid budget in relatively good times, I fear it will be almost impossible to get Australians to support government aid for other nations in the next year or so.

Christians and churches have great opportunities to work for common good.

The common good consists of far more than medical health and economics. In the next few months, Christians and churches have great opportunities to work for common good. We should look out for the weak and vulnerable around us, that is part of building the common good. It is also important to think about what we can do to help promote shared life under changed conditions. That will take some creativity. With high levels of anxiety and the temptation to bunker down, some small steps might make a big difference.

I’ve heard some great stories of Christians and churches finding ways to connect to their neighbours and serve their communities. Christians have connected with their neighbours and set up some shared communication on Facebook or WhatsApp. Churches have offered to deliver groceries and are setting up freezers with meals. Neighbours are sharing music from a distance. People have offered to help medical staff and others whose lives have become very complex over the last few weeks. Praying for our community and our leaders is one way Christians are instructed to contribute to society (1 Tim 2:1-2).

Christians are committed to the common good because God is. The Bible ends with a wonderful picture of a city populated by God’s people, secure in his protection. In the middle of the city the river of life is lined with the tree of life, the leaves of which heal the nations. Most importantly, God himself is present to bless his people and glorify them (Rev 21:9-22:5). That is what God will do in the fulfillment of all his work. In the meantime, we should do what we can for the good of our cities, towns, villages and nation.